The hip is a ball-and-socket joint made up of the femur (ball) and acetabulum (socket). The labrum is a ring of fibrocartilage attached to the rim of the socket and forms a watertight seal around the ball. The labrum has two important functions: to seal off the joint fluid inside the central part of the hip and more evenly lubricate the surface cartilage, and to stabilize the hip joint by forming a suction seal around the ball.

If the labrum becomes torn or detached from the rim of the socket, its function is compromised. This occurs most commonly due to repetitive injury in the setting of long-standing hip impingement (FAI) or hip instability (dysplasia), but may also occur from a combination of both pathologies as it is common to see dysplasia and FAI at the same time (too much bone of the ball side, not enough on the socket side). Less commonly, a single traumatic event or injury can cause a labral tear. If the labrum becomes torn or detached from the rim of the socket, its function is compromised, and it usually leads to hip pain. With certain variants of hip impingement, the labrum can become hardened, calcified, and even turn into bone (ossified). All of these abnormalities result in impaired labral function and may potentially lead to early arthritis.

If a recent MRI scan of your hip revealed a torn labrum, don’t panic, you have several options. The first step is to determine whether the labral tear on MRI correlates with any of your present symptoms. Many people undergo MRI scans for reasons other than hip pain and are incidentally found to have a torn labrum. In these cases we still perform a thorough clinical evaluation to ensure that the torn labrum found on MRI is truly asymptomatic. Patients with presumed asymptomatic labral tears may have referred pain to an atypical location (such as the buttock) leading them to incorrectly conclude that the problem is not in the hip joint, when in fact it is. If, after a comprehensive evaluation, you are deemed to have a completely asymptomatic (or minimally symptomatic) labral tear, the recommended treatment is return to activities as tolerated and periodic re-evaluation. Close re-evaluation may be recommended if you also have radiographic signs of impingement or instability.

Despite the theoretical risks of early arthritis due to a compromised labral seal, there is not enough scientific evidence to support initiating treatment for a person with a minimally symptomatic torn labrum. Surgery, however minimally invasive, carries risks and should only be undertaken when there is a reasonable medical probability of improving the patient’s experience. We always treat the patient, not the MRI finding.

There is significant misinformation being perpetuated about the significance of a torn labrum, leading to confusion among patients. A crucial distinction to make is that although the labrum is often the source of pain, it is seldom the source of the problem. Labral tears typically occur secondary to a structural abnormality in the hip. Patients with hip impingement (FAI) or hip instability (dysplasia) have altered biomechanics placing increased stress on the labrum and surface cartilage. These conditions are often present for many years and cause minimal to no pain until enough damage occurs to the labrum and surface cartilage. Fixing the torn labrum alone will not result in any long lasting relief, unless the underlying bony abnormality is addressed at the same time. Otherwise, the same process that gave rise to the labral tear will cause the repair to fail. On rare occasions, a patient with a perfectly normal hip will sustain a fall or some type of traumatic injury and tear the labrum. In these cases, the goal is to get the torn labrum to heal, assuming it has the capacity to do so, and no additional treatment may be necessary.

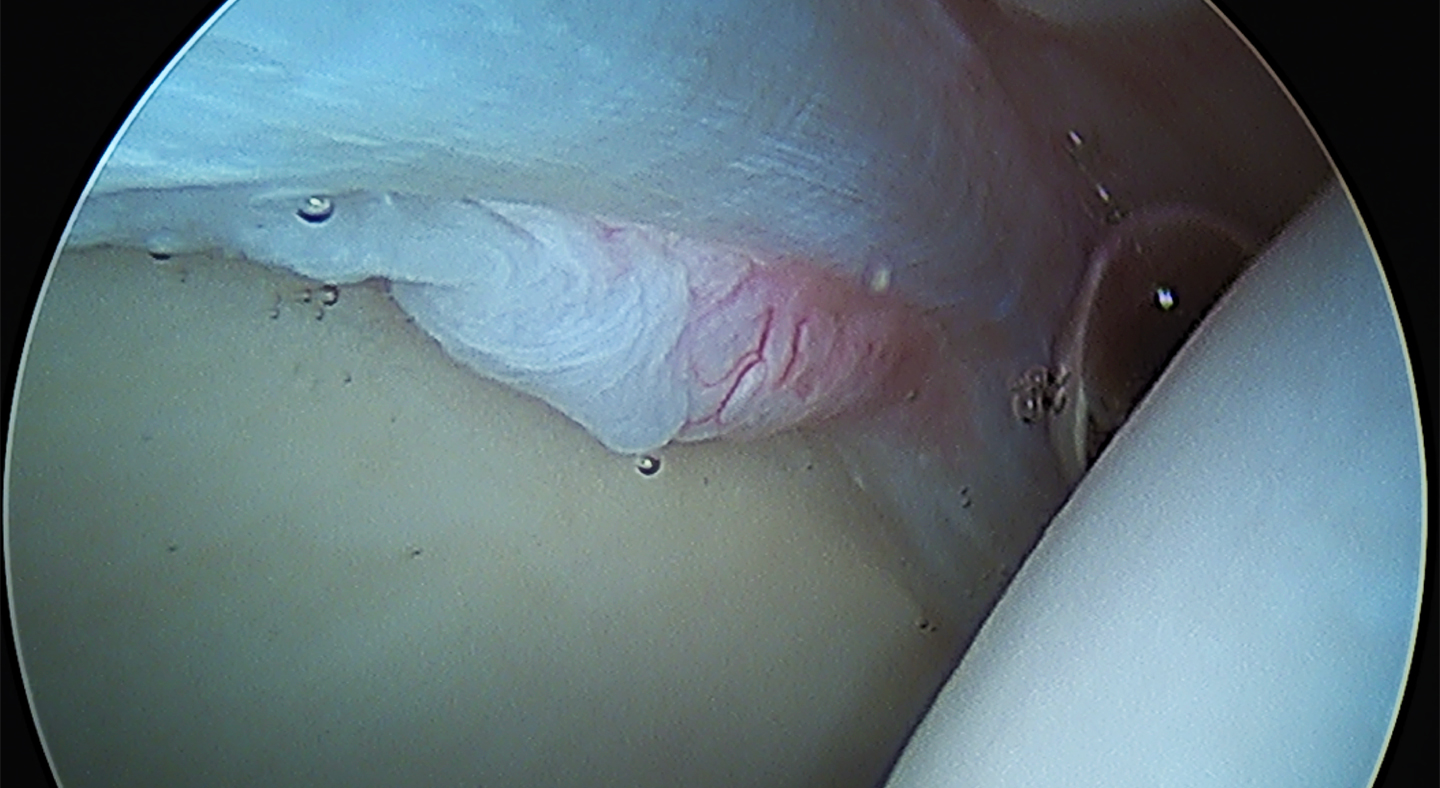

The treatment approach for a torn labrum is centered on the patient’s symptoms and underlying bony abnormality. Conservative management is always recommended first, including modifying activities, performing physical therapy, and taking oral anti-inflammatory medication. The healing process may also be accelerated with an injection of platelet-rich-plasma (PRP) into the hip joint. Patients with relatively normal hip anatomy often find these measures to be sufficient for alleviating pain and restoring function, at least for the short term. Those with significant bony abnormalities, however, typically experience short lasting and incomplete relief of symptoms, being unable to return to their desired level of activity. In these patients, the next step is to discuss definitive treatment with minimally invasive hip arthroscopy to repair the torn labrum and reshape the hip joint. Labral repair is carried out using bone anchors and suture material, to bring the torn labrum back to the rim of the socket where it will heal in an anatomic position and reconstitute the suction seal on the ball. Following labral repair, patients with hip impingement are treated with a reshaping of the hip joint using a high-speed burr to remove abnormal bone. Patients with hip instability are evaluated for additional realignment procedures (PAO and/or DFO) to restore normal biomechanics to the hip joint and protect the labrum and surface cartilage from re-injury.